When it comes to getting quality mental healthcare, people in low- and middle-income countries around the world are at a grave disadvantage, not just because of a pervasive misunderstanding surrounding mental disorders, but also due to a lack of healthcare professionals and even basic treatments for those who need them most.

“In Rwanda, for instance, a country of 13 million, there are just 12 psychiatrists and two neurologists,” says Virginia Smith-Swintosky, Ph.D., Mental Health Global Program Leader, Global Public Health, Johnson & Johnson. “Several countries have zero mental health professionals on the ground.”

As part of its longstanding commitment to neuroscience and mental health, Johnson & Johnson Global Public Health is aiming to change this bleak landscape with a big, bold goal: “As the largest, most broadly based healthcare company in the world, our aim is to bring mental health to a better place, as we’ve done with conditions like HIV and tuberculosis,” says Smith-Swintosky. “We want as many patients as possible to receive quality mental healthcare.”

Enter the Global Mental Health Scholarship Fund at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), supported through an educational grant from Johnson & Johnson, which aims to help prepare Masters in Public Health students to initiate, develop and oversee mental health programs and policies around the world, as well as to conduct and critically evaluate research on global mental health.

Launched in 2018, “the Fund offers a great opportunity to support students from low- and middle-income countries so they can take what they learn with them as they drive impact in their communities and around the world,” says Smith-Swintosky.

See how four of the Johnson & Johnson Global Mental Health Scholars at the LSHTM—each focused on a different aspect of mental health, each from a country lacking adequate resources to treat psychological and psychiatric disorders—are committed to changing the mental health landscape for all people. For Mental Health Awareness Month, they reflect on the forces that shaped them on their journey to becoming global mental health changemakers.

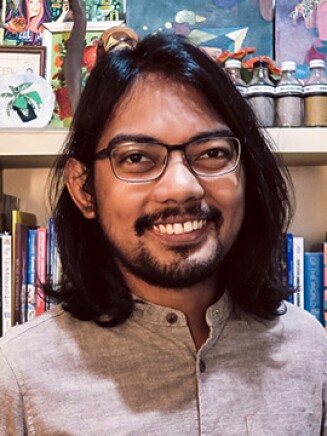

Reaching young people where they are

That’s not always the case in Nigeria, where stigma can be a big part of our culture. Some people see mental health disorders as the result of a curse or a spiritual problem, and people who struggle with them are often dismissed as ‘mad.’ Many of my colleagues in medical school struggled with depression. Some were unable to cope and dropped out. Sadly, some died of suicide.

That got me thinking about how lucky I’d been, and what I really wanted to do, which was to work with an organization that raises awareness of and reduces stigma around mental illnesses and provides the kind of community support that I was privileged to experience. When I couldn’t find one, I created Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative (MANI), a nonprofit that’s meant to increase young people’s understanding of mental illness in simple and engaging ways. For instance, we use content on social media and at in-person events to teach young people what to do if they need someone to talk with about what they’re going through while also providing them an outlet to speak to someone via our text-based counseling platform.

I used my own savings and got help from friends to launch MANI in 2016 and initially took on all aspects myself, from doing graphic design to manning our mental health help line. Five years later, we have more than 1,500 volunteers, have reached millions of people on social media and have provided free mental health support to more than 40,000 Nigerians.

By the time I applied for the scholarship at LSHTM, I had taken my organization as far as I felt I could. I needed more skills, context, relationships and exposure to resources. The scholarship made it possible to achieve this dream.

One of the most important things the program did for me was to expose me to other existing mental health research ideas—to what works and what doesn’t. Before, I was creating initiatives off the top of my head, based on my own experiences. At LSHTM, I learned that even good intentions can be harmful if you don’t test things properly. I also connected with so many organizations and experts I’d never have known about if I’d remained in my small world back home.

Right now, I’m working as the Mental Health and Psychological Support (MHPSS) and Youth Engagement Advisor for the MHPSS Collaborative, a global platform for research, innovation, learning and advocacy in mental health and psychosocial support. I’m also still supporting the growth and strategic direction of MANI. Our goals are ambitious: At the beginning of next year, we will be launching a platform that supports and scales text-based counseling and allows us to actively track mental health conditions that are on the rise. This will enable us to maintain an overview of the mental health landscape in Nigeria and support data-driven, better-targeted and more efficient advocacy. I have high hopes for the future.”

Getting help to rural areas

But when I started reflecting on my life, I realized how central mental health is to physical, spiritual and social wellness. I also saw how many other people were affected by mental health disorders during the 10 years I worked in a deeply rural area in South Africa, five of which were spent working at a district hospital and the other five spent leading a community-based rehabilitation program.

In 2014, I joined RuReSa (Rural Rehab South Africa)—an organization advocating for rehabilitation services in rural areas—and chaired the Rural Mental Health Campaign there. Mental health services in rural areas are almost nonexistent, with many psychologists, psychiatrists and rehabilitation professionals located in urban areas. People with mental health disorders often experience severe injustices, and many people lose their lives. I knew I wanted to help, and for a few years I did. I even had the opportunity to present the findings of the Rural Mental Health Campaign at the national investigation into mental healthcare services led by the South African Human Rights Commission.

Once I got that experience, I wanted to solidify it, to be in an international space, so I began looking for a program in global mental health. The scholarship made it possible for me to study abroad at LSHTM. In 2019, at age 35, I packed up my life and moved to London.

One of the greatest parts of the program was getting to know and learn from people from all over the world. Having access to all that knowledge—the professors, the lectures, the journals, the library, my classmates—was a gift, even as we found ourselves dealing with the challenges of finishing the program during the pandemic. But what we all understood was this: As difficult as the pandemic was and is, it was helping spotlight why mental healthcare is so important.

I’ve just accepted a job as an occupational therapist supporting individuals experiencing mental health issues. Thanks to the scholarship and program, I know that I’ll continue to grow and find my path on this mental health career journey. When policies and budgets for healthcare are developed in South Africa and other under-resourced nations, my hope is that more funds will be allocated to mental health. Ultimately, I am driven by the belief that there is no health without mental health.”

Bringing sensitive topics out into the open

Imbuto was founded by the First Lady of Rwanda and during my time there—first as an intern, then as a program officer—I worked to equip young people with knowledge about sexual and reproductive health and help train healthcare providers to deliver youth-friendly services in communities. I didn’t talk openly about sex with my parents growing up, and one of our goals at Imbuto was to make sure parents understood the importance of discussing these sensitive issues with their children.

It was during my four years there that I started to understand that mental health is a critical aspect of adolescent health, but I didn’t have the clinical background to explain why or how. I realized that if I could find a way to explain what goes on in the mind of an adolescent, I could make more of an impact. So I started researching programs and discovered global mental health at LSHTM.

Although it was difficult in the beginning—because of the pandemic, the whole program was remote—I now feel I have the necessary tools to integrate mental health into my understanding of adolescent health. I learned how to do research, implement programs and adapt programs that were successful in other countries to potentially work in other contexts. My dissertation was on screening for depression in young mothers during pregnancy.

When I go back home at the end of 2021, my dream is to create spaces where young people can be more aware of their own mental health as well as common mental health disorders.”

Including those on the margins

Young people are starting to talk about things like anxiety and depression in Indonesia. But the services for people with mental illness are scarce. Only about 1% of the national health budget is devoted to mental health, including prevention and treatment. In some remote areas, there continues to be a practice of stigmatizing people with mental health disorders and even chaining them up so they won’t hurt anyone.

At LSHTM, one focus is on the fundamental science of measuring mental health, innovation and policy. I’ve been deepening my knowledge by doing a systematic review of the effect of interventions that alleviate poverty on mental health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. But I also love the school’s mission of advancing innovative treatments in low-resource settings; that’s exactly what I want to learn about. And because my classmates come from many different countries, their perspectives enrich the discussion. All of us are from different backgrounds, but we are all interested in mental health, which creates conditions for learning from multiple angles.

After my studies at LSHTM, the scholarship enabled me to continue gaining global experiences. I am currently working with South East and East Asian Centre, a nonprofit that focuses on helping marginalized populations, notably to establish community mental health. We’ve tried to help some of the invisible groups here, especially migrant workers and the undocumented. We’ve been doing outreach at vaccination centers in the city, assuring people that they will still be protected despite being undocumented, providing mental health support and connecting them to basic services.

Local mental health workshops are a good place to start building inclusive community-based support for people with mental health disorders; so is strengthening the community through mental health awareness programs that aim to destigmatize mental disorders. Research and science are still our best approach, but only when people listen. The pandemic has really uncovered what happens when people neglect science.

One thing I think will help is simplifying the language of science and how we communicate results so that they can have a more widespread influence, including helping people who live on the margins. In the end, you can’t separate mental health from the burden of poverty, from forced migrations—there needs to be an integrated approach to mental health that takes all these things into consideration.”